Beyond the Brain Drain: How Diaspora Scientists Are Bridging Nations

The emigration of scientists has historically paid off for host countries, but as networks of diaspora scientists become stronger, the benefits are flowing back to scientists’ homelands and enhancing cooperation in both directions.

Scientific cooperation spans the globe, as illustrated in this map of collaborations based on co-authored publications | Olivier H. Beauchesne, olihb.com. Data from Science Matrix & Scopus

Scientific cooperation spans the globe, as illustrated in this map of collaborations based on co-authored publications | Olivier H. Beauchesne, olihb.com. Data from Science Matrix & Scopus

Uprooting and moving to a new country takes gumption — a quality also in large supply among successful scientists and engineers. It follows, then, that in Silicon Valley 44 percent of engineering and technology ventures launched between 2006 and 2012 were founded by at least one immigrant, as the Kauffman Foundation has reported. And, in the United States, more than a quarter of foreign-born workers with college degrees work as scientists or engineers, according to the National Science Foundation.

Historically, the emigration of scientists and engineers has benefitted the host countries, raising concerns about brain drains and “innovation exoduses” from the countries that scientists leave behind. But a growing movement by AAAS and others to organize and strengthen international networks of expat scientists and engineers is changing that. Properly leveraged, these networks could help drive innovation and solve problems in scientists’ home regions, and improve diplomatic relations between countries.

The Potential of Science Diasporas

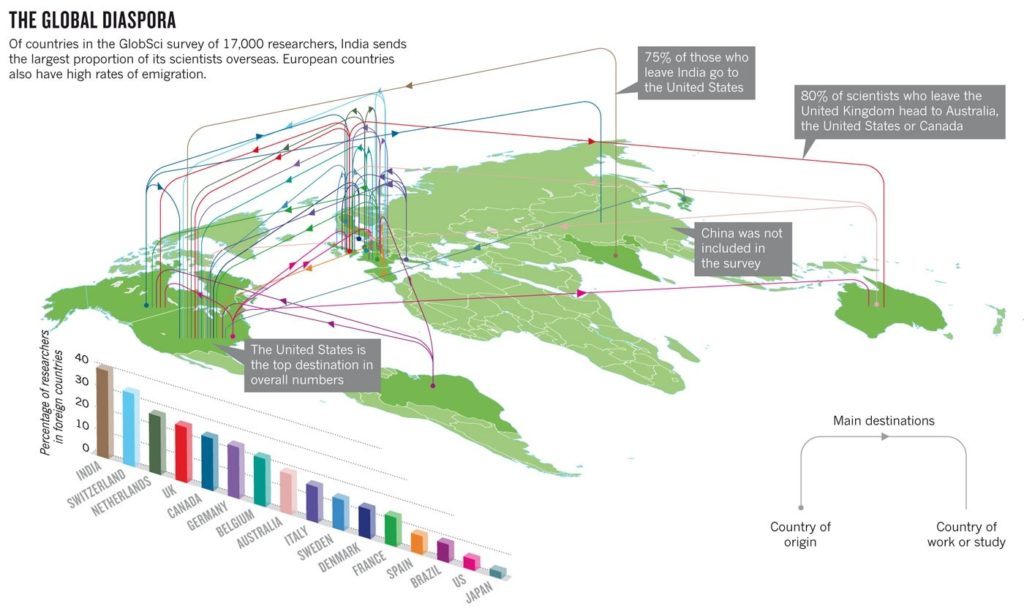

Scientists are a mobile bunch to begin with, often relocating to take advantage of funding opportunities and professional collaborations. According to a Nature survey the United States is the top destination for scientists from abroad, especially from India, which sends roughly 40% of its scientists overseas. Switzerland, Canada and Australia each host even higher proportions of foreign scientists than the United States does.

The “GlobSci” survey asked around 17,000 researchers in 16 countries about their movements. | Nature

Along with other educated groups, scientists have also fled their home countries upon finding themselves on the wrong end of totalitarian regimes. Revolutions in Cuba, Eastern Europe and Iran, for example, propelled scientists and other professionals abroad in the 20th century. Some, such as Polish molecular biologist and Solidarity activist Maciej Żylicz, were targeted for their political activities: when the communist government in Poland imposed martial law in the early 1980s, Żylicz was faced with the choice of leaving the country or being imprisoned.

Żylicz told his story at a 13 February meeting on “Science and Engineering Diaspora Engagement” held in conjunction with the AAAS Annual Meeting in Chicago. The event was organized by the Network of Diaspora in Engineering and Science (NODES) with the Embassy of the Republic of Poland and the Foundation for Polish Science. NODES is a partnership between the U.S. Department of State, AAAS, the National Academy of Science and the National Academy of Engineering, which supports diaspora communities by sharing knowledge and best practices, and convening diaspora groups and linking them with useful tools and institutions. The meeting drew representatives from countries including Poland, Japan, Brazil, Iraq, Tunisia and others.

“Like so much of American life, the story of innovation is a story of immigration….”

William J. Burns, Science & Diplomacy

After seven years in the United States, Żylicz returned to Poland, where he is now President and Executive Director of the Foundation for Polish Science. In the United States, many scientists of Polish origin have their focus fixed firmly on their homeland as well. Piotr Moncarz, an engineering professor at Stanford and academic co-director of a program called Top 500 Innovators of Poland, described how the program brings teams of early-career Polish scientists and engineers to U.S. universities to develop technology-transfer skills that will help them translate research into new products and services.

Many governments are trying to cultivate homegrown talent and lure scientists back from abroad, said William Colglazier, Science and Technology Advisor to the Secretary of State, who was part of the NODES panel. The European Union has “clearly gotten the message” and is offering desirable funding package for attracting top researchers, and Japan is also trying to reinvigorate its efforts to make the country an appealing place for scientists to work, Colglazier said.

He expressed concern that the United States is losing its luster in the eyes of the world’s best scientists and engineers, in part because of cumbersome visa and immigration policies. “If the United States wants to engage more internationally, which is the goal that I and my colleagues have, we have to find a way to remove some of these barriers,” Colglazier said.

For Polish Biochemist, Political Exile Led to Science Reform at Home

Until martial law was imposed in Poland in 1981, Maciej Żylicz was able — despite some difficulties — to conduct his research on bacterial proteins while protesting his country’s communist government. But when the crackdown came, Żylicz, who was the chairman of the University of Gdansk’s Solidarity unit, had to go into hiding after organizing a strike at the university. In an autobiographical essay in IUBMB Life, Żylicz describes how, lacking access to a telephone and knowing that letters were censored, he sent a letter to a Polish colleague working in the United States, requesting a reprint of one of his works. In the space where the volume and page number would go, Żylicz wrote the code of the relevant U.S. visa form. The U.S. professor understood the clue and sent Żylicz an official invitation to work in the United States and the necessary visa documents. Żylicz gave himself up and eventually received his passport and a one-way ticket out of Poland.

Żylicz spent seven years at the University of Utah and Stanford University, where he came to appreciate the benefits of a competitive, national funding based on peer-review system. “This is something scientists in Poland weren’t talking about,” he told the audience at the February NODES meeting in Chicago. After martial law was lifted and amnesty proclaimed, Żylicz moved back home and along with other returning scientists established a similar funding system and other merit-based initiatives for supporting the best science in Poland. Żylicz is now President and Executive Director of the Foundation for Polish Science and Head of the Molecular Biology Department of the International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology of Warsaw. “My American dream came through in Poland. If you are a very good scientist and hard-working, it is now possible to open your own lab [and further] your career,” he said.

Professor Maciej Żylicz | Courtesy of the Foundation for Polish Science

Long-Distance Collaborations

It’s becoming increasingly clear, however, that scientists don’t always need to live in the countries where their research is focused. For international partnerships that spread the benefits of science around the world, the science, technology and innovation diaspora “remains a vastly untapped resource” William J. Burns, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, has written in the AAAS quarterly, Science & Diplomacy.

In his December 2013 article, Burns describes a variety of diaspora “knowledge networks,” such as the Turkish American Scholars and Scientists Association, the Wild Geese Network of Irish Scientists, and the Ethiopian Physics Society in North America, through which diaspora scientists organize scientific exchanges, educational programs, networking and other opportunities that build capacity and encourage innovation in both the scientists’ home countries and the United States.

Other partnerships tackle more specific problems. With support from the Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) Science, a collaboration of USAID and the National Science Foundation, diaspora scientists in the Unites States are working with colleagues in their home countries to develop low-carbon cities in India, address the impacts of climate change on tropical wetlands in Colombia, and design effective emergency management systems for post-disaster relief operations, according to Burns.

Projects like these have great potential, Colglazier said at the NODES meeting, “but they will require concerted effort.” Practical issues, such as forging the necessary linkages with home governments and their scientific institutions — not commitment from diaspora groups — tend to pose the greatest challenge, he said.

Diasporas and Diplomacy

The benefits of these diaspora networks ultimately extend beyond science. Scientific cooperation can be an essential element of foreign policy, allowing countries to focus on areas of mutual interest even if they are in conflict on political topics.

Many opportunities exist for the United States to engage with Iran in areas of science and medicine, and researchers in the two countries have collaborated on topics such as food-borne diseases, neuroscience and drug abuse, noncommunicable diseases, health disparities and bioethics.

The Iranian diaspora would seem to be a natural source of expertise; Iranian Americans, for example, are well-educated overall, and highly represented in science, engineering and medical fields. Another diaspora-related event organized by AAAS in January 2014 looked at the potential for involving Iranian diaspora scientists in science diplomacy efforts with Iran.

Other participants at the NODES event also described their efforts to engage scientists in countries where political relationships are strained. Mark Rasenick of the University of Illinois at Chicago has with AAAS organized multiple meetings between scientists in the United States and Cuba on neuroscience and other topics. Others in the room also saw great potential for science diplomacy with Cuba, in particular relating to its thriving biotechnology industry.

Szafra Margolin Lerman, an Israeli scientist working in the United States, described the challenges and payoffs of organizing the Malta Conferences that bring together scientists from across the Middle East, including Israel. The conferences have led to important collaborations on issues of regional importance, such as water and solar energy, but Lerman, who is President of the Malta Conferences Foundation, described several considerations the organizers must make in order to enable all the scientists to participate. For example, because equality is very important, plenary lectures are given only by Nobel laureates, and all other participants give oral or poster presentation. Spouses, also, are not invited. “There are different nuances you have to be very aware of to make these conferences a success,” said Lerman.

Source: https://www.aaas.org/